Title page began to be widely deployed in manuscripts after print as a new medium of textual reproduction became known and popularised. Manuscripts before the introduction of print on a large scale usually did not employ a title page. A text would be normally referred to by its first words, and an initial letter or word of a textual unit would be visually distinguished on the page. Initial page or incipit page would often be a feature of a medieval manuscript, sometimes illuminated, decorated or rubricated, or at least highlighted by the use of larger and/or square script.

Many textual units would often be planned to be comprised within one codex and textual contents had a linear development. Thus, since one medieval codex may have many texts and many initials or marked incipits, a title page for the full manuscript would not be necessary nor very useable. The appearance of the technology of movable print, as a different manner of reproducing texts on a large scale, gave an impetus to encode bibliographical information in individual copies of texts and to do it in a concise way. Title pages became a useful and practical solution to contain main information about the production circumstances and the content of the book.

Before the printed book manuscripts tended to encode bibliographical metadata, or at least parts of it such as date and place of manuscript production or name(s) of scribe(s), in the colophon located at the end of the codex. Some early modern manuscripts do keep colophons too, depending on the aesthetic or cultural pressures under which they were made. But scribes could also choose to work with a format more and more familiar to readers from another medium and employ a title page, especially if the book copied comprised of one text only or if it was a coherently structured collection of texts. Thus, the metadata moved to the front of the handwritten book for aesthetics or for a marketing reason, to compete in the bookshops with a book in a printed format. It provided a visually recognisable form of organising information about the volume at hand.

By the mid-sixteenth century, title page became a standard feature of the printed text. Collaterally, it became a common feature of manuscript books, at least those which were produced for sale or for public circulation. Title pages include, besides titles, the name of author(s), the place and date of production, and the name of scribe(s), although not all of these element are always present together. It could also be expanded to include additional information, especially visual, as they were often decorated.1

As a space to provide metadata, title page became delimited by its cultural and political rhetorics. Both in print and in early modern manuscript, title page provides an opportunity to provide all kinds of information, also false or otherwise misleading. For one, manuscript could copy title pages from their printed exemplar and thus not offer information on the actual physical object, but on the circumstances of its exemplar. But not only that. Title pages were material sites that emerged in print under pressure from the authorities to control book publications, and yet were often employed to circumvent such control. Title page could thus be used by book producers as handy bibliographical devices to negotiate authority, be it of the textual content of the book, of book authorship, or of the book publishers and makers. As such, these bibliographical devices contain often simple, but not simply objective information.2

- On the history of printed title page see A.W. Pollard, Last Words on the History of the Title Page (London: Nimmo, 1891); Margaret Smith, The Title Page: Its Early Development 1460-1510 (London: British Library, 2010); Alastair Fowler, The Mind of the Book: Pictorial Title Pages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

- See Jacob Blanck, The Title Page as Bibliographical Evidence (Berkeley, CA: UoC Press, 1966).

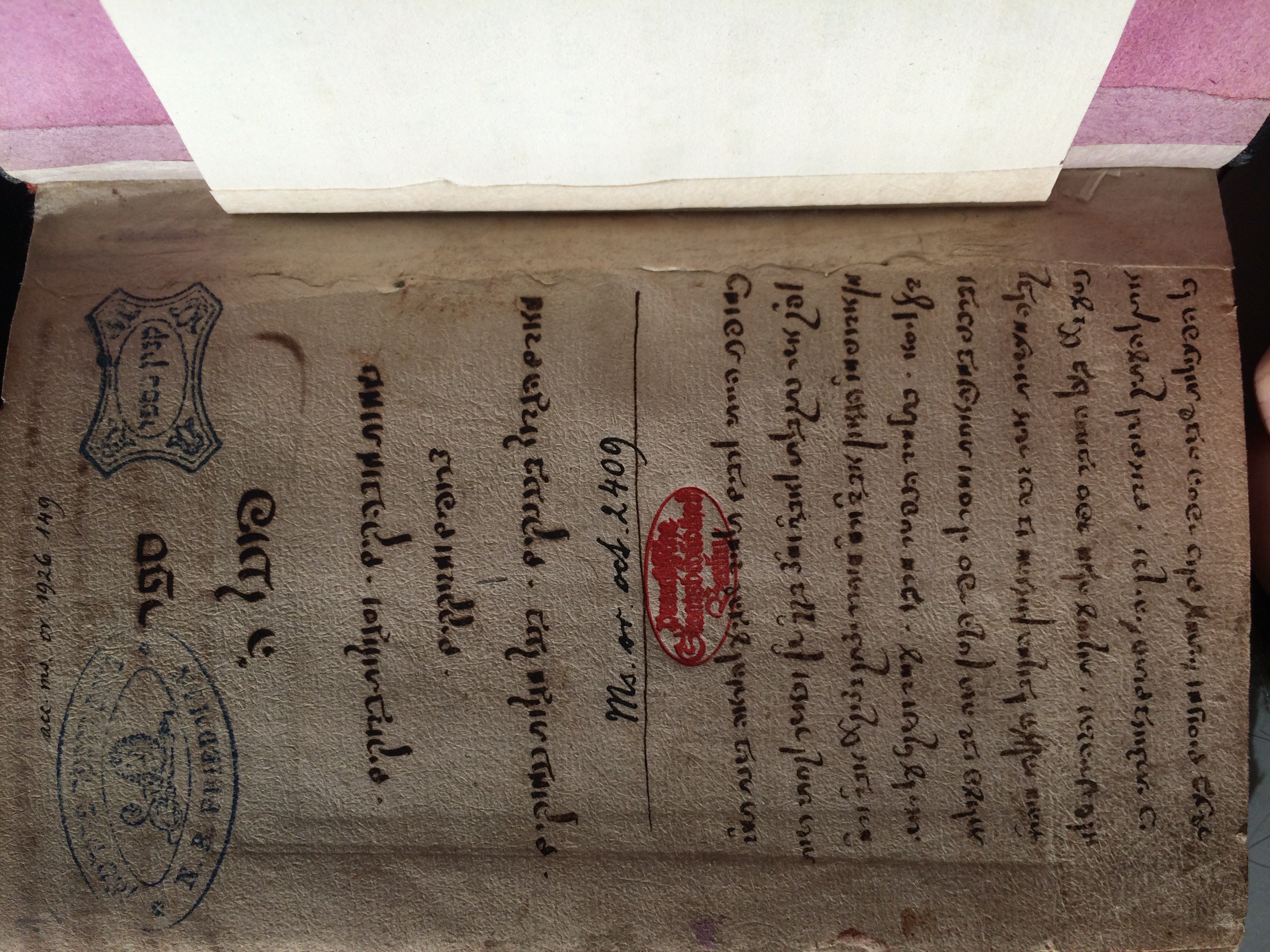

EXAMPLE 1: SBB Or. Oct. 2409

A small handwritten publication held by Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Or. Oct. 2409, contains an example of a title page with just a few lines, yet loaded with quite some cultural and social significance. The manuscript’s title, Sefer Po’el ha-Shem, is followed by a short description of its content of: “wonderful names, tested qualities [charms], and purified [letter] combinations, by the greatest of men, the author of Megallot ‘Amukim.”

This short title provides a description of the contents of the book, advertising them properly — these are divine names and charms for practical use. But the strongest stamp of authority comes from the authorial attribution of the text to the author of Megallot ‘Amukim. In fact, the title of this text should read Megalleh ‘Amukot, and its apparent author was one of the most famous Polish kabbalist, Nathan Neta Shapira of Krakow in Lesser Poland (1585-1633). However, the reader finds the full name of the alleged author only later, in a scribal introduction. The actual book title takes only about half of the page, which is divided in two parts by a horizontal line. The rest of the important metadata of this manuscript follows under the line, and is inscribed in smaller semi-cursive script. This page is thus an instance of the merging of a title page with a scribal introduction, a format that was present in those Ashkenazi handwritten codices of mid- and late 17th century that were intended for circulation or later remediation. For one, it exceeds one page of a typical title page, and yet it provides all the information that would be necessary to properly designate and advertise it.

General Description

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

Or. Oct. 2409

Paper

1687

Hebrew

History

Origin: Greater Poland (Leszno, Lissa)

Formerly: N.B. Friedman

Sources

A. Paluch, “Compilation and Textual Transmission of an Early Modern Kabbalistic Commentary: Nathan Neta Shapira of Krakow and Megalleh ‘Amukot” in A. Bar-Levav, R. Margolin (Eds), Jubilee Volume Presented to Professor Moshe Idel, forthcoming

Catalogue record of the National Library of Israel

Codicology

Paper, octavo

28 folios, foliated

Palaeography

Script: Ashkenazi semi-cursive and cursive script, of mid-17th century

Hand(s): one hand, uniform

Content

Textual units: Sefer Po’el ha-Shem (fols. 1-24v), ‘Avodah rabah (fols. 25r-28v)